The new movie “Oppenheimer” continues to break records at the box office, and much to the surprise of members of the local community, three of the men involved in the Manhattan Project graduated from Park University.

J. Robert Oppenheimer was a theoretical physicist and director of the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico during the Manhattan Project during World War II. Called the ‘father of the atomic bomb’ he was responsible for the research and design of the bomb.

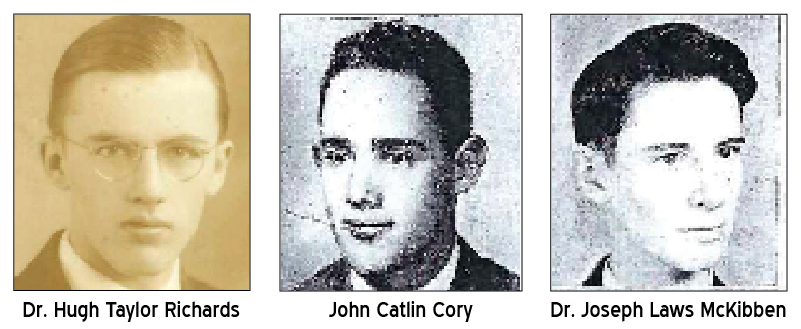

The university’s Archivist, Dr. Timothy Westcott, was familiar with Dr. Hugh Taylor Richards’ connection to Park because of long generational ties to the university, along with his Richard’s biography.

“The connection of John Catlin Cory was mentioned in his 2017 obituary and is the only known reference to the Manhattan Project,” Westcott said. “Dr. Joseph Laws McKibben’s relationship came to be researched as one of Park’s outstanding alumni.”

When Westcott evaluated McKibben’s alumni file, he became aware of his role and historical importance as being known as the ‘man who pushed the button’ on the Trinity test of July 16, 1945.

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon conducted by the United States Army on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project.The implosion-design plutonium bomb was the same type of bomb detonated over Japan at the end of WWII.

The three Park graduates who worked on the Manhattan Project include John Catlin Cory, who was born in Leavenworth, Kan. He studied chemistry at Park College (now Park University. He developed an interest in nuclear science and pursued independent studies using the works of Niels Bohr, a Danish physicist and Nobel Prize in Physics winner who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory.

After graduation, Cory was immediately recruited as a researcher for the early stages of the Manhattan Project. He reported for duty and became a key researcher at the time when the project was actually located in Manhattan, N.Y. World War II had commenced, and despite a request to take a deferment as a critical contributor to the war effort, Cory resigned from the Manhattan Project and joined the Army Air Corps. After training as a navigator for the B-24 ‘Liberator’ and commissioning, he was assigned to the 15th AAF operating from Italy. He flew numerous combat missions and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism, the Air Medal with multiple Oak Leaves for meritorious service, and numerous campaign stars.

Joseph Laws McKibben was from Wellsville, Mo., and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in physics. He went to Los Alamos in 1943. He detonated the first man-made nuclear explosion at an isolated desert site near Alamogordo N.M. in July, 1945. When he became ill in 1941 and was brought back to his home in Wellsville to recuperate, no one knew about the health threats of radio activity. He later was diagnosed with cancer and volunteered to be a guinea pig at a cancer research laboratory.

The illness of Dr. McKibben is thought to have been brought about by his close contact with atomic energy. The white corpuscles of his blood stream were being affected. When he had sufficiently recovered to return to his position, a lead shield was placed between him and his atomic equipment.

Later in his life he was asked repeatedly if he regretted pushing the button, but he never answered the question. “We well realized in 1942 that the atomic bomb might be a terrible weapon,” McKibben said. We were anxious to be first. We really hoped this wouldn’t work, but we succeeded. They started looking around for somebody to do the job and it fell on me.”

Hugh Taylor Richards grew up in Wisconsin and studied physics at Park College. In 1943, he was called to Los Alamos, to work on the Manhattan Project. He was among the first group of scientists assembled at Los Alamos to design and construct an atomic bomb. Later he was in charge of the neutron measurements for the first atomic bomb test in July 1945.

He worked at developing special cameras which were placed at varying distances from ground zero to measure radio activity of fission fragments.

In 1993, he wrote the book, “Through Los Alamos, 1945: Memoirs of a Nuclear Physicist.”

A British physicist told him that intelligence reports indicated that the Germans were working on a fission bomb. Perhaps a bomb was not feasible, but if the Germans could even produce large amounts of radio activities, the military shock possibilities of dropping these on troops or cities might be important and Richards agreed to undertake an Office of Scientific Research and Development project to measure energy spectra of fast neutrons.

Dr. Richards was active in the formation of the Association of Los Alamos Scientists to educate society about the perils and potentialities of the new era.

While researching the documents of the three graudates at Park who had roles in the Manhattan Project were of great interest to Westcott, he said there are volumes of interesting stories related to Park and the wider communities of Parkville and Platte County that remain untold.

“I don’t specifically have favorites because each project is unique in its own narrative,” Westcott said.

He has been the archivist at Park for more than a decade.

His resume includes: professor of history; Chair, Department of Culture and Society; Associate University Archivist; Program Coordinator for the Programs of History and Military History; Faculty Advisor to the Roy V. Magers History Club and Phi Alpha Theta (National History Honor Society) Zeta Omicron Chapter; ROTC Academic Advisor; and Director, George S. Robb Centre for the Study of the Great War at Park University.

“The profession of an archivist is closely aligned with that of a historian,” Westcott said. “When I was performing research during my graduate studies, the more I became engaged with archives and archivists in that research, interrelating the professions of history and archival science became a passion.”

Park University has for more than a century collected and preserved documents and artifacts related to Park College, and later, Park University, City of Parkville and Platte County history. Westcott said there are hundreds of thousands of documents in the archive and there is no way at this time to record a definite number.

During his time as an archivist at the university, Westcott has been surprised and fascinated by numerous examples of archive material.

“The most noted have been Park’s connection to the RMS Titanic, admission of Nisei students in 1942, and participation in the V-12 Naval College Training Program during World War II,” he said. “Lesser known stories reflect Park’s long missionary and ministry histories and how these ambassadors served and influenced numerous countries. global regions, and local communities, and Park’s almost 150-year history of educating U.S. veterans that have served, or are continuing to serve our nation.”

The biggest challenge for Westcott in his archivist career is advancing digitization projects that highlight the voluminous collections held, and arranging and delivering those artifacts and collections to the general public.The rewards are numerous and include engaging with students, staff, alumni, colleagues, and others in disclosing the narratives of their collected history, and an additional reward is acquiring collection donations to the archives.

The possibility of discovering more fascinating connections to history make each day exciting for Westcott.

“My duties, related to the archives, are only one of many that awaits on a daily basis However, the opportunities to interweave all of my daily tasks into educating students and the public is rewarding.

As far as the film Oppenheimer, which is the highest-grossing World War II movie ever made, surpassing ‘Dunkirk” and “Saving Private Ryan,” Westcott said he enjoyed the first two hours and its historical depiction of establishing the overall Manhattan Project, but he thought the last hour felt somewhat disconnected from the earlier segment.

“Unless the viewer has detailed knowledge of Oppenheimer’s biography, the continuous footage between the security clearance interrogations and the congressional hearings may slog out the film,” Westcott said.”The film provides a foundational narration of one selected person’s connection to a singular historical event in a specific period. The film could furnish a bridge between the fast diminishing World War II generation and present-day individuals.”

Unsure if the local connections might have enhanced the interest people in the area have shown for the film, Westcott said he hoped that if the local audience has seen or hasn’t seen the film, that there is reflection that these former Platte County residents and students at Park College, were extremely instrumental in the Manhattan Project overall and the Trinity Test specifically.

When asked as a professor of history, his opinion on the Manhattan Project, the Trinity Test and the dropping of the bombs in Japan as far as being a decision that overall saved many lives and was considered the wisest choice at the time, Westcott’s view is, “The passage of time provides a deeper reflection on direct action in a definite time period and further research and outcomes. Recent opinions have begun to question President Harry Truman’s decision which could be generational and social advocacy.”

Joseph McKibben had a simple answer to the moral questioning of the results of the Manhattan Project which are still being debated 78 years after the end of WWII. “We had a job to do and we did it. One of the difficult things these protester types have to understand is that it was a war situation. We were in a war.”